Work began on the mechanical side of the project, but this was also a tough time for funding the restoration. This was not like restoring a 356 as I would do most of the grunt work myself. This was an expensive undertaking so as my family grew it also significantly limited the funds that were available for the restoration of 0141. Several times I had to stop or delay the process until I had a little spare change in the bank.

Luckily I had previously assembled most of all the rare parts and pieces to put 0141 back to its original state, except for a few items that I would need to fabricate. I have not spoke much about the cost of trying to replace some of these rare parts today, but to give you some idea, if you were to try and replace just a set of lightweight wheels, you could be in the $15,000 range. The rear shock mounts would need to be made and I again turned to Warren Eads who was kind enough to have his removed to be used to fabricate new ones from. The shocks themselves were re-built by the Koni factory in Holland as they again were one off parts which could not be found anywhere.

The transmission was going to be a greater challenge as it was also the most unique in that it was Porsches’ first five speed box but in a split case. These were only used on the 550A with the shift lever, or hockey stick, coming out of the shift housing in a reverse position as opposed from directly out of the rear of the shift housing.

To complete the gear box I needed a ring & pinion, all three shift rails, and various gear sets. A stash of gear sets were found in Japan and over time I was able to locate all the items except for the shift rails. Warren couldn’t help here as his car was now stored in Europe so he could participate in vintage racing activities on the other side of the pond. This took some talking, but I was able to convince one 550A owner to allow for the disassembly of his transmission, remove the shift rails and have new ones made. I had five sets made and actually found customers for three of the sets which paid for all the fabrication costs.

The wiring harness needed replacing and on a business trip to southern California I visited the owner of Y&Z’s out in Riverside. I showed him the old harness which was still fairly complete and revealed a combination of woven and plastic sheathing. He thought this was most interesting as this was the time the factory was shifting over to all plastic coverings but this harness had both. He assured me he could duplicate the harness including the odd combination of sheathing. He then gave me an estimate and the new harness arrived in Du Bois 6 months later.

As Billy proceeded he mentioned several times of the foresight of the coachbuilders. When assembling the brakes, which have large air scoops on the backing plates for brake cooling, they align perfectly with the cool air ducts coming from the front openings in nose bodywork of 0141. These are large 60 MM brake drums which are unique to the 550 and 550A. While 60 MM brakes were available on GS and standard on GT cars, these were different. When installing the oil system the hard lines which run from the engine compartment to the front oil cooler were already installed. These are impossible to install once the body is molded to the frame. There were also small hidden doors made in certain areas of the underside body to allow for access and ease of installation of other components, such as the brake master cylinder and clutch slave cylinder.

As my family grew we found ourselves taking vacations in Jackson, imagine that. While in Jackson I would always take a day and drive over the hill to visit Billy and 0141. On one of these excursions I was able to convince my wife to tag along. She has no interest in the car project but it was under the guise of going on a hike that got her into the car. As we arrived at Bill’s shop she waited in the rental car while I inspected the progress on the Spyder. Bill then closed up his shop and took us about 5 miles out of town to a trailhead. This is beautiful mountainess country and the trail had a very aggressive altitude gain up and into a box canyon. About 3 hours later we arrived at the destination of our hike. Bill wanted to show us the site of a B-24 crash. While on a training flight the crew of a B-24 got caught in this box canyon and slammed into a sheer rock wall. As we approached the base of this wall I began to find small pieces of aluminum and then a debris field of twisted metal and radial engines. I often wondered where that huge Carter carburetor came from on Billy’s mantle, and now I knew.

Once you get into a project like this you can be overwhelmed by all the little bits and pieces you find you must have hand made. The time and energy that goes into duplicating bell cranks for the throttle linkage or the emergency brake cable guides at the firewall and this list goes on and on. Slowly all pieces have come together with attention to correctness and functionality. One of the reasons for employing Bill Doyle on the mechanical portion of the restoration is certainly his abilities, but also he has Spyders in and out of his shop periodically which have been reference points for much of the fabrication that has taken place

I have tried to gear the restoration with two goals in mind, vintage racing and concours. This mandates not only attention to authenticity, but also the considerations for special equipment in vintage racing. I had a custom 3 point removable roll bar made during the re-bodiment and when the fuel tank was made we installed a door at the bottom so a rubber bladder could be inserted.

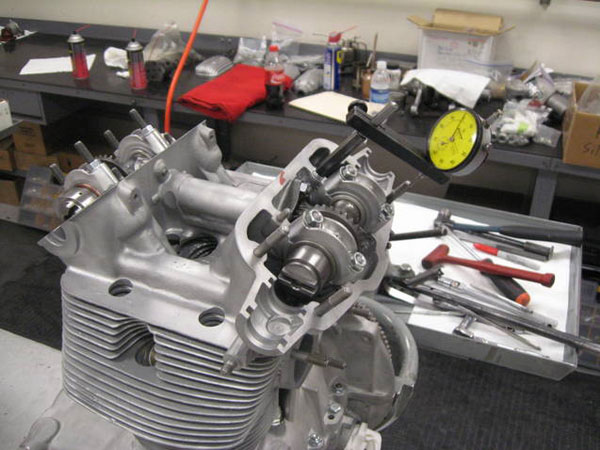

The last and most important piece of this project is the re-manufacture of the roller bearing engine. The roller bearing crankshaft is the foundation for the overhead, 4 cam motor which will power 0141. This is a very complicated part and used in all Porsche’s racing Spyders, but you certainly did not want to have one explode on you while at high revs. Today there are certain updates you can utilize to give added strength to this crank and we have employed all of them. It is also the valve train that is most interesting. Each intake and exhaust bank has its own camshaft driven by timing shafts and bevel gears. There is a “lay shaft” which drives off the crankshaft then engages the “A&B” gears out to each head. Again, very complicated but was the means by which Porsche could ensure very accurate valve timing at high revs. The designer of this engine, Dr. Fuhrmann, also employed what is known as “gear hunting”. The engine must spin 36 times before all timing gears mate up to the same tooth again. This prevents pre-mature gear wear and prolongs the life of the valve train.